How important is Pascoe’s identification as Indigenous? That night it was everything. When he was a student at university, Aboriginal people were not even counted in the census.

It was also an audacious leap from his own experience: Pascoe had grown up white in inner Melbourne in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, missing the profound hardship and discrimination experienced by Aboriginal Australians. Pascoe’s words bonded him powerfully to the shared pain of Indigenous dispossession and the tragedy of Aboriginal deaths in custody and youth suicide.

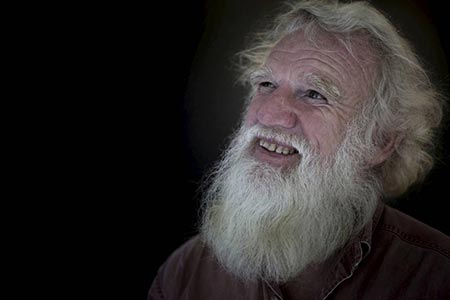

I just feel like I’m being choked and enough of our people have had that experience, so I’m not going to be the next.” Warming to this theme he told NITV: “I can’t wear ties. “I have gone out my way for you mob,” he joked. Of all the awards he’d received, this one, he said, made him the most proud because it came from “our people”.Īmidst the glitter and the black tie splendour of the awards at Sydney’s Star casino, Pascoe made light of his shambolic ways. He hadn’t owned a suit in all his then-71 years, he said, and only got one because he was told he needed “something formal”. Pascoe’s award for person of the year was the climax of the night, recognising the Dark Emu author for his “significant contribution” to the advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait people. At the end of 2018 Bruce Pascoe was in the spotlight for yet another honour, this time at the National Dreamtime Awards, a premier event celebrating Indigenous achievement and broadcast by National Indigenous Television (NITV).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)